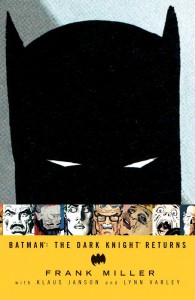

Through chronological coincidence, my next comic entry is an excellent choice to follow the previous one. Having seen where the Batman got his start, The Dark Knight Returns gives me a chance to see where he ended up. And where he ended up isn’t pretty.

Through chronological coincidence, my next comic entry is an excellent choice to follow the previous one. Having seen where the Batman got his start, The Dark Knight Returns gives me a chance to see where he ended up. And where he ended up isn’t pretty.

One Robin, Boy Wonder has left him and a second has died in his arms. He has been retired for ten years, due to a nebulous agreement that retired or co-opted the other superheroes at the same time (save for Superman, who is now employed by the US Government). Gotham is overrun with crime, filled with gangs of teenagers who own the streets and can make and carry out threats at will. Commissioner Gordon is facing mandatory retirement, and among most of the talking heads on TV, the rehabilitation into society of such criminal masterminds as Two-Face and the Joker are cause for celebration at the success of the system rather than horror and fear at its failure.

Whether because of the declining morality of the youth population, because of guilt over his involvement in Harvey Dent’s (that is, Two-Face’s) inability to cope with his freedom and subsequent return to villainhood, or simply because he doesn’t feel like an entire man without the Bat, the re-costumed Bruce Wayne hits this socio-political climate like a thunderbolt, taking on the gangs, old enemies and old friends alike, condemned by cartoonish liberals for what he is doing to criminals and by cartoonish conservatives for what he is doing to law and order, and joined at an opportune moment by a new Robin. It’s a very raw take on an old man’s unstoppable crusade against everyone who brings society down instead of building it up.

Being raw, though, it does have its flaws. The stories are held together by the world around them, but seem pretty episodic in nature on their own. The art, while excellently frenetic, occasionally lends itself to being difficult to follow. It’s hard to really like any of the characters on a consistent basis (with the exceptions of Gordon and Robin). But flawed or not, it has the power of its rawness, and I’m not a bit surprised that the Batman mythos since this work has owed far more to it than to anything that came before, outside of those initial episodes that first set the character down on cheap pulp. (And which, frankly, were a lot like Frank Miller’s vision in this book. It’s much easier to imagine a straight line between the two graphic novels I’ve read that doesn’t go through Adam West than one that does.)

Also: as you’d probably expect, the Joker (newly revived from catatonia at the news that he once more has a nemesis worth committing senseless murder for) steals every scene he’s in, whether it be praising the media for being his own personal fan club, highlighting all of his criminal activity on the evening news so he doesn’t need to keep track of it himself or whether offhandedly promising to kill everyone within sight of his face and being laughed at for, well, joking (he was not, of course). It’s easy to make an argument that the Batman needs a Joker, an enemy that the forces of law cannot hope to cope with, that justifies his vigilantism. This story makes the far more compelling argument that the Joker needs a Batman; because, if there’s no chance of failure, is there really a point in proceeding on the basis of sociopathy alone?

[Late-breaking full disclosure: I actually read this in the Absolute format, but it contained two books, of which I still in 2015 have not read the second one. So it’s hard to produce a link and image for only half of a book, much less one that is by now long out of print.]