Gene Wolfe is an author whose work tends to exist right at the outer limit of what I can wrap my mind around. I swim through his novels, working to keep my head above water the whole time, and the nature of that effort leaves me with a limited perspective of the story’s surface from moment to moment. Not only that, but I’m aware of unplumbed depths of added meaning in a vague, unformed way; I guess I’m aware of it only to the extent that I can tell there’s a whole lot more happening that I’m not aware of. Possibly this all sounds unpleasant, and maybe it would be except for three things. The parts of the story I can grasp (a sizable amount of plot, bits and pieces of characterization, shadows of literary influences, and the faintest impressions of theme) have always been very entertaining; the prose is good enough to make mention of; and the parts of the story I can’t grasp exercise my reading brain. I’ll read the Book of the New Sun sometime again, and I’ll have benefited by that. Also, the Malazan series. (Which I’m sufficiently behind on now that I’ll probably need to start over. Oh, well.) Umberto Eco does this to me as well, but without quite as much enjoyability on the front end. I guess my point is that being challenged is cool.

Gene Wolfe is an author whose work tends to exist right at the outer limit of what I can wrap my mind around. I swim through his novels, working to keep my head above water the whole time, and the nature of that effort leaves me with a limited perspective of the story’s surface from moment to moment. Not only that, but I’m aware of unplumbed depths of added meaning in a vague, unformed way; I guess I’m aware of it only to the extent that I can tell there’s a whole lot more happening that I’m not aware of. Possibly this all sounds unpleasant, and maybe it would be except for three things. The parts of the story I can grasp (a sizable amount of plot, bits and pieces of characterization, shadows of literary influences, and the faintest impressions of theme) have always been very entertaining; the prose is good enough to make mention of; and the parts of the story I can’t grasp exercise my reading brain. I’ll read the Book of the New Sun sometime again, and I’ll have benefited by that. Also, the Malazan series. (Which I’m sufficiently behind on now that I’ll probably need to start over. Oh, well.) Umberto Eco does this to me as well, but without quite as much enjoyability on the front end. I guess my point is that being challenged is cool.

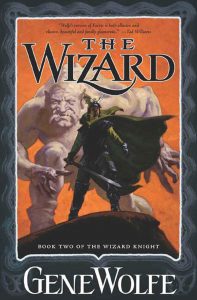

However, it makes for difficult reviewing, because I don’t like to toss plot elements willy-nilly, and at the same time I have little else to reference right now. When I read The Knight last year, I indicated this same difficulty. Reading The Wizard was akin to leaving the public pool and taking a dip in the ocean. Which is ironic when you consider that water imagery was rife in the former volume. …and fire imagery as well. Whereas this one was much more about earth and air. So, hey, look at that! I figured something out right here in the middle of typing. Which would be cooler if I could attach some direct relevance to the revelation. But it definitely proves my point about the mind-exercise. Anyway, I’m going to see about minimizing the self-satisfaction and getting back to the review, now. I trust this will be taken kindly by all six of my readers.

Sir Able’s continuing adventures in Mythgarthr and its surrounding realities have expanded from faeries, knights, and dragons to include giants, angels, unicorns, Arthuriana, and the Norse pantheon. As difficult to integrate into my understanding of the world as these were, the (at first glance) simple plot was harder still. The first half of the book is the story not of Able, but of his companion squires and knights. The emerging lesson of the section seems to be that we are not what people call us; we are what we are, whether people call us such or not. But people will tend to call us what we are. For example, Able is a knight because he determined to be so and lived his life that way, not because anyone dubbed him or acknowledged him. Despite that from his first appearance in the book he refuses to use any powers , Able is called a wizard now by all who spend time with him because his inner reality shines through. These examples together with a spoiler from later in the book make me pretty confident that this sometimes struggle and sometimes congruence between what is and what is perceived is another important theme of the story. But again, just because I can see it doesn’t really mean that I’ve yet been able to plumb its depths and understand the buried point to it. Which, amusingly, is kind of a mirror of the theme right there.

I said it at the beginning, and I’ll say it again. Hard books are cool. Which is not an excuse for the incomprehensible mess of the previous paragraph, but it is an explanation of sorts. (Seriously. I’ve edited a lot, and well, to get it to what you see now. The original would have made you weep with frustration.) So, yeah, they’re cool, but they’re also hard. Thus, by executive decree, it’s going to be all graphic novels from now until Harry Potter.