[Note: I’m not concerned about spoiling the 1978 movie, because, come on. but I’ve found it impossible to discuss the remake without going in depth, so below the cut, expect heavy spoilers.]

[Note: I’m not concerned about spoiling the 1978 movie, because, come on. but I’ve found it impossible to discuss the remake without going in depth, so below the cut, expect heavy spoilers.]

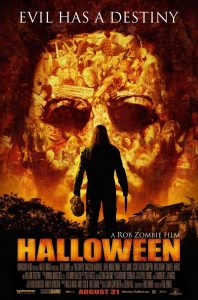

How do you remake a practically perfect horror movie? You don’t change things around to suit yourself, and you make sure to have some kind of hook that explores something that’s never been explored before. If those sound contradictory, well, I maintain that they are not or at least don’t have to be. For a completely random example, Rob Zombie’s Halloween remake: it has to include a scary kid who killed his whole family; then was placed under the care of a psychologist for 15 or so years, who became obsessed with him; then broke out of the sanitarium to find his baby sister, who has no idea that their relationship exists. While hunting her, he has to be confronted by sex-crazed teens over and over again, so that he will kill them in re-enactment of the murder of his older sister. The scary kid, his doctor, and his sister have to come together in a deadly climactic confrontation. Maybe it’s formulaic, but it’s a pretty good formula, and one that John Carpenter all but invented.

Except it also has to have something new, lest it risk the abject soullessness of the Psycho remake. The good news there is that Rob Zombie is good at theme, even if the theme is that random violence is essentially unavoidable and can fall down upon your head at any moment. Which, in retrospect, fits Halloween pretty well, so that’s alright. As for what he added, it was personality. We see Michael Myers in those early years when he had a face and a voice, and we see his family, and as a result we see his genesis? Yes and no. His life sucked, of course, and that’s not an excuse to turn into a psychopath. But in the wrong person, it can be a trigger, and I’m okay with that. And I get that Dr. Loomis giving up on him would have triggered his escape and search for validation in the one person left on earth who could love him, and certainly the one person left on earth who he loved, even more importantly. But Loomis’ ultimate failure to connect with the boy was inexplicable, and as such shouldn’t have made it onto the screen. Having stated that baldly, I’m now forced to admit that there’s no good transition between Loomis starting Michael’s treatment and his giving up over a decade later without showing some of the failure in between.

All of which leads into my big complaint with the movie, of which the previous issue is merely a symptom. As interesting and creepy as it was to watch a realistic portrayal of a young American psychopath, the better angle is the one that Loomis himself took: that the Devil lives behind Michael Myers’ eyes. Michael’s humanizing factor is his obsession with his sister, and that’s enough. Humanize him more, and suddenly there are all kinds of sticky questions about why shooting him barely slows him down, and why he always gets back up eventually, no matter how much has gone into knocking him down. Humanize him more, and it becomes impossible to explain why Loomis had such a failure to connect with his patient; when he’s just the faceless mask, you don’t wonder why, you just accept it.

However, the mask imagery made up for the flaws. Michael was as obsessed with masks as he was with his sister; within just months of his incarceration in the psych ward, his walls were covered with the masks he had made. A mask allowed him to become a different person, and eventually it wasn’t just a metaphor. Michael without a mask was a troubled boy with moments of sweetness. Michael with a mask was a soulless killing machine, lashing out at anyone who he perceived to have crossed him. And sometimes lashing out for no discernible reason at all, or at surrogates for those who had crossed him. Disturbing to watch the light go out in his eyes, yes, but very compelling. It was a good enough contrast study that, if I could only let myself believe that the mask could sap Michael of his physical humanity as effectively as it stripped him of his emotional humanity, I’d no longer have any complaints about the remake and have to instead be considering whether or not it had surpassed its progenitor.

As it is, Carpenter’s version wins, because I’m not stuck in a circle where I alternately suspend disbelief and question what I’m seeing as even vaguely plausible. Also because of its extraordinary sequel, though.

Pingback: Shards of Delirium » A Nightmare on Elm Street (2010)